Next year’s earnings estimates for US companies peaked in April for large-caps and in June for small-caps. Given Powell’s resolve to significantly reduce the current four-decade-high inflation – no matter what the cost to jobs and the economy – the downward revision cycle has just begun.

The sell-side has brought out its scissors. Estimates for both this year and next for S&P 500 (large)-, 400 (mid)- and small (600)-caps have peaked.

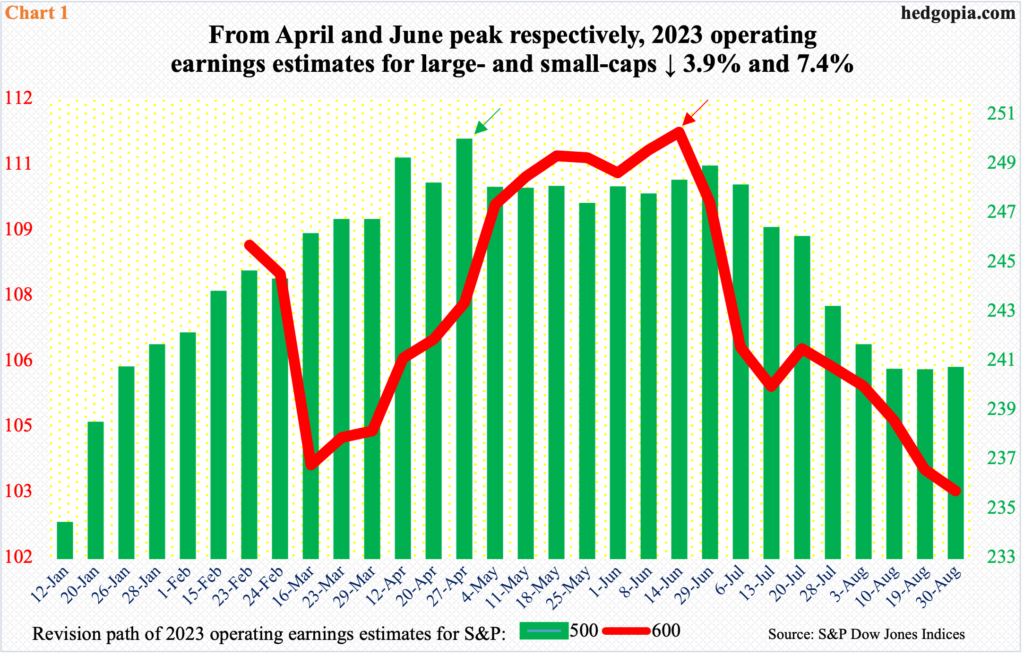

With 2022 halfway through, investors at this point are more interested in what next year might bring. At the end of last month, 2023 operating earnings estimates for S&P 500 companies stood at $240.65, down from the record $250.12 posted as of April 27. Incidentally, 2022 estimates peaked at the same date – $227.51 versus the current $209.99.

(Similarly, S&P 400 estimates for both this year and next peaked at $186.81 and $207.54 respectively as of May 18 and were $178.98 and $199.11 at the end of August. Chart 1 does not include estimates for mid-caps.)

Small-cap estimates peaked earlier for this year than next. As of April 12, this year’s estimates hit $92.70, which has now been revised lower to $84.19. Next year’s crested at $111.23 as of June 14 and were $103.02 as of August 30.

Ironically, earnings, on a nominal level, have gotten help from the ongoing inflation as corporations try to pass on rising costs to consumers.

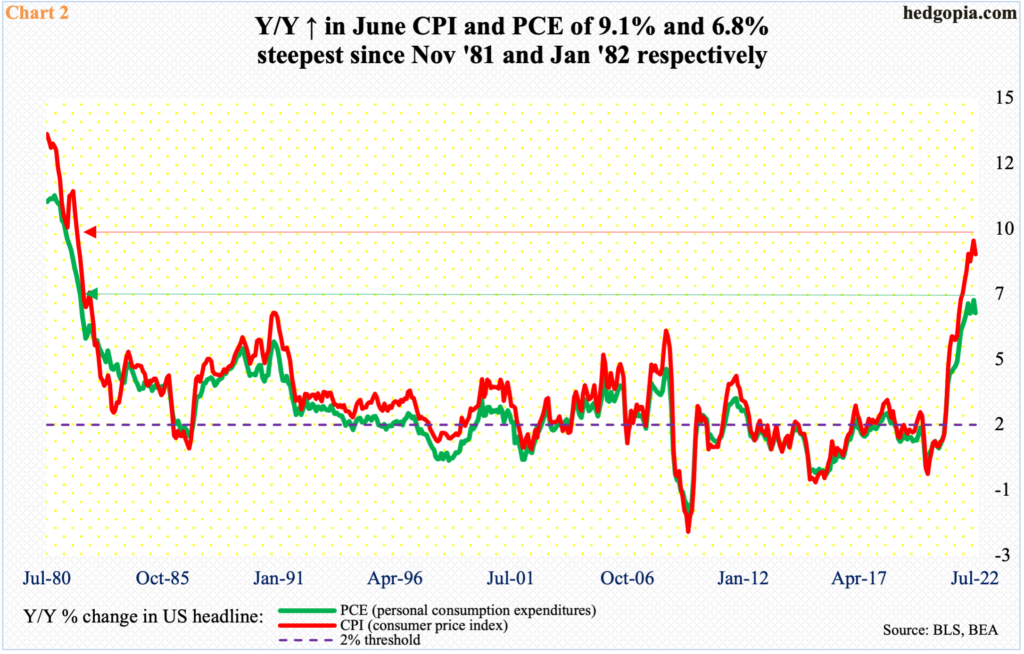

Consumer inflation is red hot. In the 12 months to July, the consumer price index and the personal consumption expenditures respectively rose 8.5 percent and 6.3 percent. This is slightly down from June’s 9.1 percent and 6.8 percent, which represented the steepest price increases since November 1981 and January 1982, in that order (Chart 2).

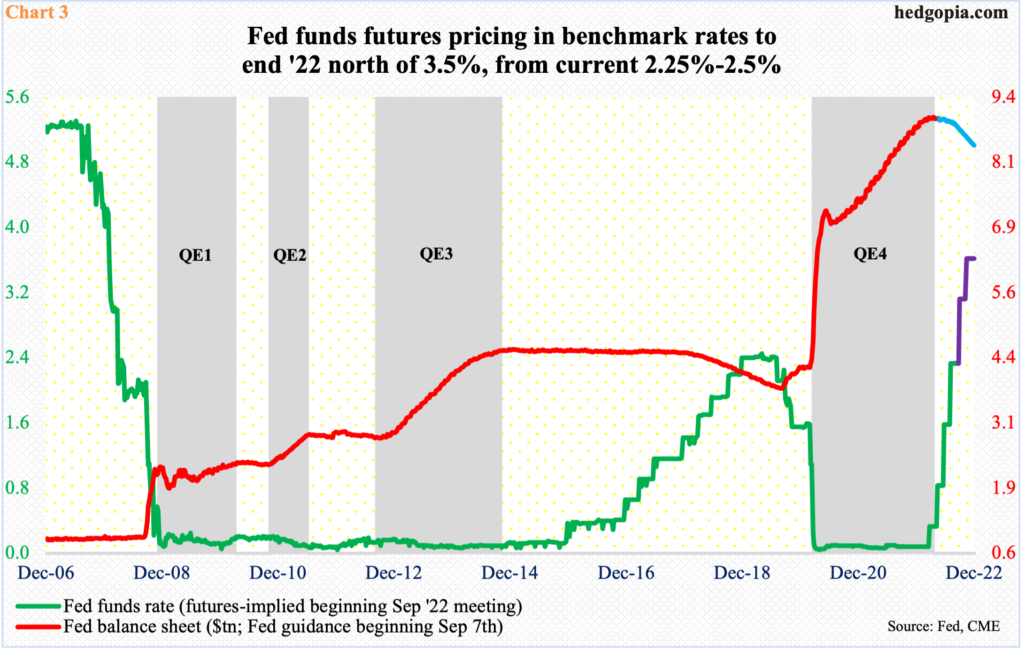

Inflation remains uncomfortably high, and the Federal Reserve, which once ignored the risk saying it is transitory, is now on the case. So far this year, it has raised the fed funds rate four times – by a couple of 75 basis points, and a 50 and 25 each – to a range of 225 basis points to 250 basis points. More hikes are on the way.

At Jackson Hole later last month, Jerome Powell, Fed chair, strongly pushed back against any notion of a pivot. After the July 26-27 FOMC meeting, markets began to dial back expectations for rate increases.

In the futures market, traders now expect the benchmark rates to end north of 3.5 percent by the end of the year (Chart 3). This is taking place even as the central bank is reducing its bloated balance sheet.

It is possible the Fed pauses after rates approach four percent, or thereabouts. In all probability, the four hikes thus far are yet to filter through the economy. Regardless if this is enough to significantly lower demand or another round of tightening follows, inflation is unlikely to take a significant hit until end-demand gets hurt.

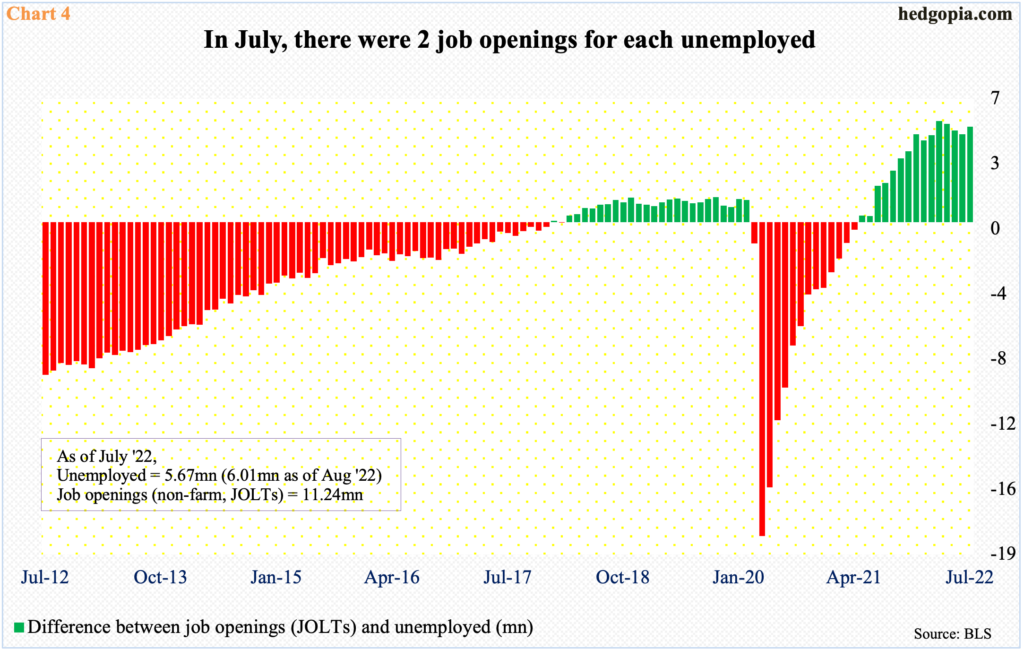

Several recent data points point to a softening in demand, but the jobs market remains healthy. The US economy produced 315,000 non-farm jobs in August for a monthly average in the first eight months of the year of 438,000, versus the monthly average last year of 562,000.

There are still two openings for an unemployed person. In July, there were 11.2 million non-farm job openings versus 5.7 million unemployed (Chart 4); the latter did rise to six million in August even as the former peaked at 11.9 million in March.

Weakness in economic activity is imminent.

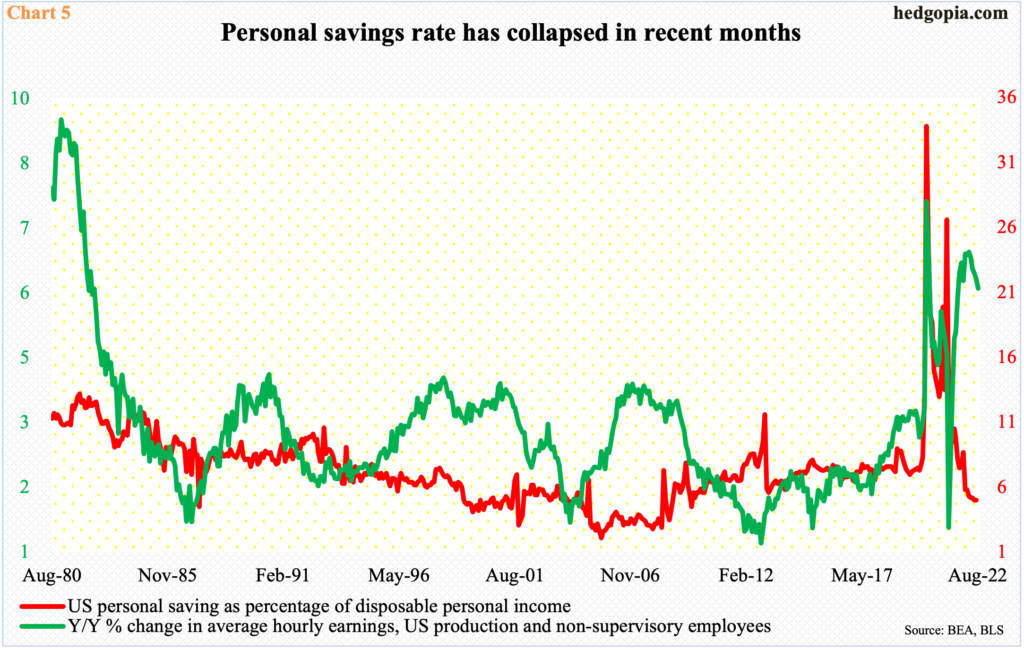

Importantly, the personal savings rate has taken a hit. Of course, savings ballooned to unsustainable heights in the early months of 2020 because of fiscal stimulus, but they are now back down to earth.

In both June and July, the savings rate reached five percent – a 13-year low (Chart 5). This despite the fact that wage growth has picked up momentum. In August, the average hourly earnings of production and non-supervisory employees grew 6.1 percent, which is softer than March’s 6.8 percent pace but much stronger than the three-handle increase seen in the early months of 2020.

The point in all this is that the Fed is not going to let up until inflation meaningfully heads back down, and this is not going to occur until end-demand softens. This is bound to impact corporate earnings. The downward revision trend rightly anticipates this. But, as things stand, next year’s estimates probably are not priced right for the amount of softness that lies ahead.

Thanks for reading!