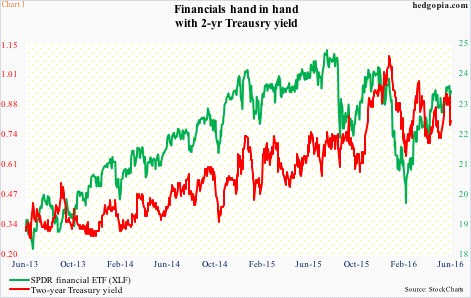

The correlation between financials and the two-year Treasury yield is tight. The latter tends to be sensitive to Fed action.

In recent months in particular, the two-year has been on a roller-coaster ride trying to keep up with FOMC members’ constantly shifting bias toward interest rates’ future path… which has alternated between hawkish and dovish. XLF, the SPDR financial ETF, follows along.

Simplistically, banks borrow short and lend long, meaning their assets are of longer average maturities than their liabilities. The steeper the yield curve, the better it is for them. Ordinarily, if the Fed feels confident to raise short-term rates, the economy has to be in good shape, which then tends to put upward pressure on longer-term yields.

That is the premise behind the green and red lines in Chart 1 moving together. But this does not always work out this way. Of late, short rates have rallied more than their longer-term cousins, resulting in a flatter yield curve.

Regardless, XLF continues to maintain a tight relationship with the two-year yield.

Last Friday, they both took a hit.

The non-farm payroll in May was a huge disappointment, up only 38,000, with downward revisions to the tune of 59,000 in March and April.

For at least a couple of weeks prior to the jobs print, several regional Fed presidents, some voting some non-voting, were strongly advocating for higher rates. Even Janet Yellen, Fed chair, in a May 20th interview at Harvard University, said an interest rate hike would probably be “appropriate” in the coming months. Fed funds futures were beginning to place higher odds on future interest-rate hikes.

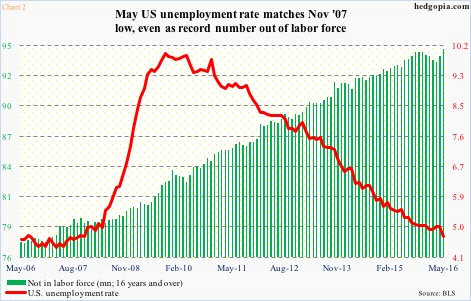

Then came the dismal May report. At the same time, the unemployment rate dipped to 4.7 percent, matching the low in November 2007. Just focusing on the unemployment rate, it looks like the economy is operating at full employment. But a record 94.7 million people are not in the labor force (Chart 2).

The jobs picture is muddy at best, and has been that way for a while. Momentum in non-farm payroll has been in deceleration. The monthly average in the first five months this year is 150,000, versus an average of 229,000 in all of 2015 and 251,000 in 2014.

With this as a background, the recent uptick in hawkish tone particularly among regional Fed presidents is atypical. There is a palpable change in sentiment.

Post-jobs report last Friday, Loretta Mester, Cleveland Fed president, said gradual rate hikes remain appropriate. Come Monday, Eric Rosengren, Boston Fed president, described the May report as “disappointing” but still expected sufficient economic growth to justify a gradual removal of accommodation. Also on Monday, Ms. Yellen, although at her non-committal best, said the jobs report was concerning, but potential rate hikes would be gradual and would happen “over time.”

In some measure, it makes sense for the Fed to be trying to fill its empty monetary quiver with arrows.

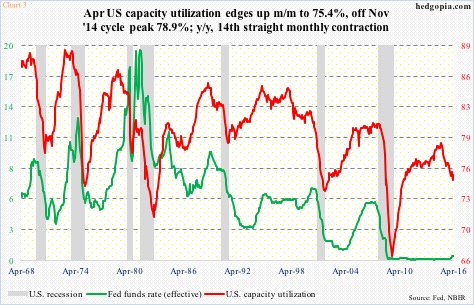

The unemployment rate may not have dipped below five percent for all the right reasons, but is indicative of a tight labor market. The recovery itself will soon complete seven years. Several data points, such as corporate profits and capacity utilization, have peaked cyclically.

In fact, it is rare for the Fed to start tightening when capacity utilization already made a cycle peak and is in decline. Yet, this is what occurred last December, when for the first time in nearly 10 years the fed funds rate was increased by 25 basis points. Utilization peaked at 78.9 percent in November 2014, with April at 75.4 percent (Chart 3).

The Fed is behind the curve and has been for a while.

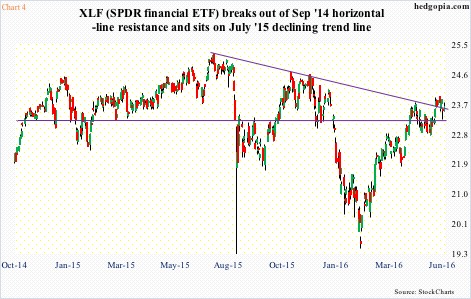

If this is what is driving them, then odds are they will try to squeeze in one or two hikes. In this scenario, XLF likely attracts bids. Last Friday, it bounced off of September 2014 horizontal-line support and rallied further on Monday to literally sit on July 2015 declining trend line (Chart 4).

Should it come to pass, this will be an opportunity to unload XLF… or some other strategy using options. The cycle is getting long in the tooth, and the economy probably is not in a position to cope with higher rates, regardless they would be rising from near zero. This concern is depicted very well in the long end of the yield curve, with the 10-year yielding 1.7 percent.

Thanks for reading!