June’s stronger-than-expected payroll print has the potential to change the Fed’s interest-rate outlook for the remainder of the year. Markets still expect at least two 25-basis-point cuts this year, including one later this month. Should Chair Jay Powell wish to let markets know they are being too demanding, he will have an opportunity to do so in this week’s Humphrey-Hawkins testimony. This can have implications for a whole host of assets, not the least of which are equities.

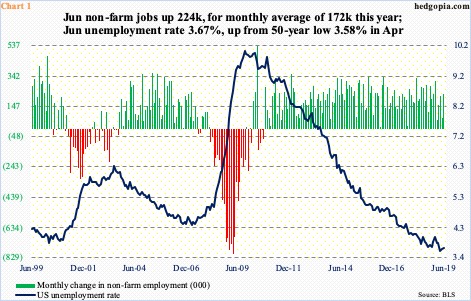

Once again, the US jobs machine proved its resiliency, snapping right back up after one month’s weakness. May only produced 72,000 non-farm jobs. This was the second sub-100,000 month this year, with February at 56,000. But June produced 224,000 jobs, for a monthly average of 172,000. This is down from the monthly average last year of 223,000 but should be considered decent given the economic cycle just completed a decade. The June snapback arguably is perhaps enough not to earnestly push the Fed into an easing cycle. The unemployment rate inched up to 3.67 percent in June; April’s 3.58 percent was the lowest since December 1969 (Chart 1).

At least that is how the sovereign bond market reacted post-jobs report Friday. The 10-year Treasury yield (2.05 percent) rallied 10 basis points in that session (Chart 2). Earlier on Wednesday – a doji session right on the daily lower Bollinger band – rates had dropped to an intraday low of 1.94 percent, which was the lowest since November 2016. A potentially bullish weekly hammer showed up last week – the second in the last three.

Yields peaked last October at 3.25 percent. The 131-basis-point decline since that high has probably priced in an easier Fed.

Before last Friday, fed funds futures aggressively priced in a 25-basis-point cut each in July and September and maybe another in December. After the jobs report, traders continue to expect a cut each in July and September, while odds of a cut in December dropped. As far as July (30-31) is concerned, markets are 100 percent sure a cut is coming. Friday, reacting to jobs, the two-year T-yield – most sensitive to monetary policy expectations – jumped 11 basis points to 1.87 percent. Traders are confused.

This is also true with equities. In the bond market, rates gradually rose Friday. Equities, on other hand, took it on the chin early on but by close recouped most of the losses. The S&P 500 large cap index within the first 75 minutes was down 0.9 percent Friday but ended the session only down 0.2 percent. The session low nearly tested Monday’s mini-breakout, when the prior high from June 21 was surpassed (Chart 3).

Stocks are taking the cue from fed funds futures, which continue to believe the Fed would give inflation the benefit of the doubt.

The Fed has a dual mandate – maximum employment and price stability. Post-Great Recession, the former has fared well (Chart 1) but not the latter. The Fed has a two-percent inflation objective. Since May 2012, core PCE – the bank’s favorite measure of consumer inflation – rose year-over-year with a two handle only once, which was July last year (chart here). Inflation, including core CPI, has trended lower for a year now. Inflation expectations peaked right around then.

Chart 4 pits the University of Michigan’s expected change in inflation next year with the 10-year inflation breakeven rate. They have both been trending lower since last year – the former in August at three percent and the latter in May at 2.14 percent, versus 2.70 percent in June and 1.69 percent last Friday, in that order.

Subdued inflation – at least going by government statistics – enables the Fed to lean dovish, if the need be. In the June (18-19) meeting, FOMC members seemed to open the door to the possibility of easing. Back then, job creation had just disappointed in May. Inflation was already trending lower. Markets firmly priced in at least a couple of cuts this year. Then came the strong June report. The Fed now finds itself painted in a corner.

The FOMC meeting is three weeks away. Given June’s strong payroll showing, the burning question is, should the Fed just accede to market demands or wait for more data? Should it opt for the latter, Mr. Powell has an opportunity to do so in this week’s testimony.

In this scenario, repercussions will be felt across asset classes. If the Fed does not cut later this month, the 10-year yield for instance has room to continue to rally. Nearest resistance lies at 2.36 percent, and after that 2.62 percent; the latter is major (Chart 2). As a matter of fact, rates are likely to react the same away even if the Fed cuts in three weeks but signals that more cuts are not forthcoming.

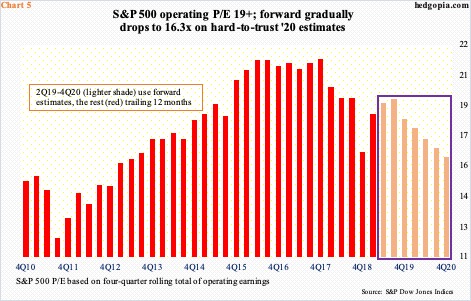

Similarly, stocks, as mentioned earlier, have priced in aggressive cuts. If this scenario does not pan out, readjustment – or multiple revaluation – is the path of least resistance. As things stand, the S&P 500 currently trades at just north of 19x operating earnings. This drops to 16.3x on ’20 estimates (Chart 5). But it is anyone’s guess if they can be trusted. In March, these companies were expected to earn $186.36, which has now been revised lower to $183.74. Estimates for this year were $177.13 last August, now only $163.60. This raises the possibility of valuation rerating, should markets begin to rethink their rate-cut expectations. This could very well begin this week, should Mr. Powell decide to put his foot down.

Thanks for reading!