Easy money is here to stay. That was pretty much the message Chair Powell delivered this week. The US economy is up to the gills in leverage. A sustained rise in interest rates will hurt. The Fed will try to stem this through the use of its balance sheet.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell is laying the groundwork for continuation of the prevailing monetary stimulus. On Monday, Pfizer (PFE) said its coronavirus vaccine was more than 90 percent effective. If this first analysis holds up, then mass vaccination can begin in the US next year, and with that the economy can begin to get back to normal. Investors aggressively bought that thesis this week, as a whole host of assets got rerated.

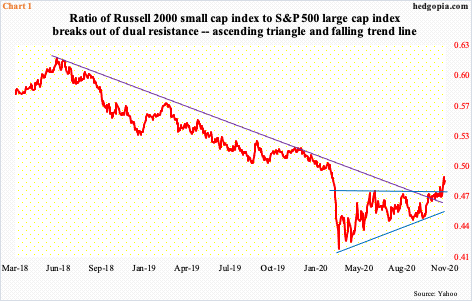

The S&P 500 large cap index rallied 2.2 percent this week, while the Russell 2000 small cap index jumped 5.8 percent. The Nasdaq 100, on the other hand, fell 1.3 percent. Investors rotated from growth to value. Small-caps inherently have larger exposure to the domestic economy versus their larger-cap brethren which are also internationally exposed.

A ratio between the Russell 2000 and the S&P 500 just broke out. The ratio had been trending lower since peaking in June 2018. It bottomed in March this year, with higher lows. But rally attempts kept getting sold at 0.47, which gave way on Monday. Friday, it closed at 0.49. Earlier in mid-October the trend line in question was taken out.

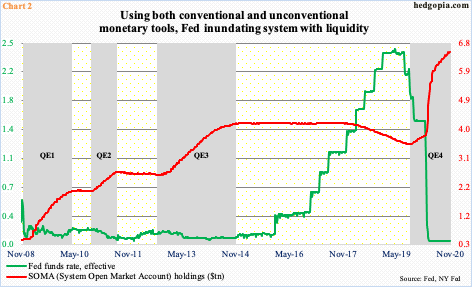

In a scenario in which the economy begins a sustained recovery, the Fed in due course could think about rolling back its stimulus program. As of Wednesday, it held $7.18 trillion in various assets, which is less than $2 billion from a record set three weeks ago. From late February, the balance sheet has expanded by a tad over $3 trillion.

The level of stimulus created by the Fed is highlighted in Chart 2. The fed funds rate remains near zero, even as SOMA (System Open Market Account) holdings stand at $6.51 trillion. The latter has gone parabolic since March.

But speaking at a virtual panel discussion at the European Central Bank’s Forum on Central Banking Thursday, Mr. Powell pretty much said the easy money would continue. “Even after the unemployment rate goes down and there’s a vaccine, there’s going to be a probably substantial group of workers who are going to need support as they’re finding their way in the post-pandemic economy, because it’s going to be different in some fundamental ways,” he said. “My sense is that we will need to do more and that Congress will need to do more.”

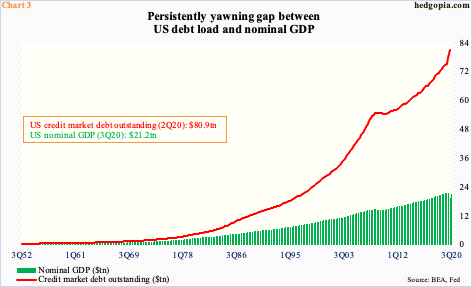

He argued that the economy we knew is probably a think of the past. “We are recovering, but to a different economy.” While true, the fact remains that the Fed has its back against the wall. As leveraged as the economy is, with national debt north of $27 trillion, corporate debt at $11 trillion and household debt north of $16 trillion, among others, higher rates will provide a massive headwind to the economy. The gap between total outstanding debt and nominal GDP continues to widen (Chart 3).

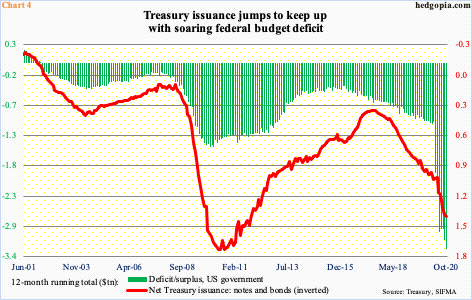

In the meantime, the US budget deficit has gone parabolic. In the 12 months to October, the government spent $3.3 trillion more than it took, versus $1 trillion in red ink a year ago. This obviously causes more debt issuance. In the 12 months to October, the Treasury issued $1.4 trillion in notes and bonds, which has followed the deficit higher (Chart 4).

The Fed has been aggressively buying up these securities. In the week to Wednesday, it held $3.87 trillion in Treasury notes and bonds, up $14.5 billion for the week. Early March, these holdings were worth $2.03 trillion. Even with all these purchases, the 10-year Treasury yield (0.89 percent) rose to 0.98 percent on Monday, up from 0.5 percent early August. The uptrend cannot continue, hence continued need for monetary stimulus – both conventional and unconventional.

Thanks for reading!